Music by Titans - The Unanswered Question by Charles Ives

Exploring truth, beauty, and goodness within the world of classical music

Piece: The Unanswered Question

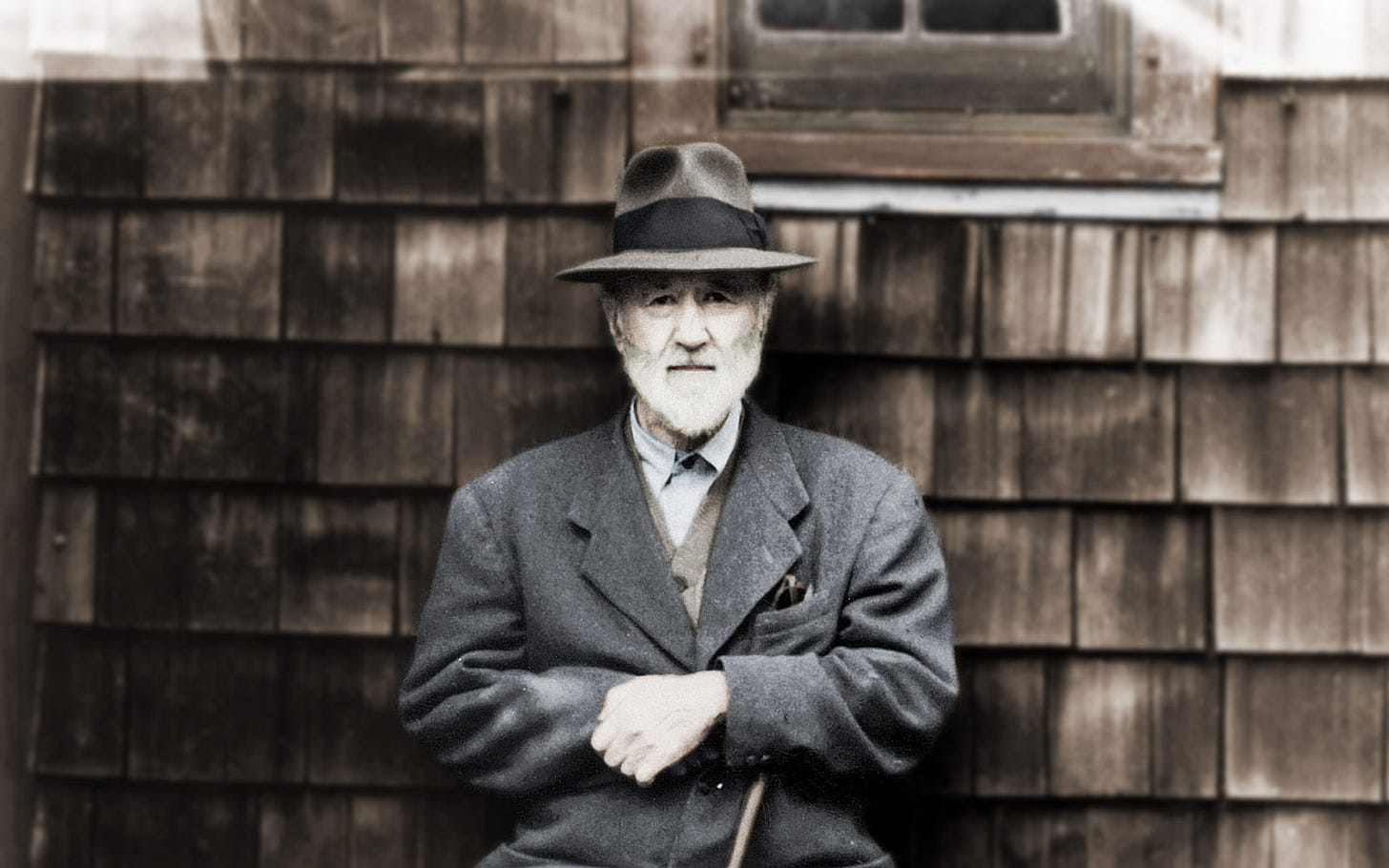

Composer: Charles Ives

There is a digital photo editing technique called “bad photoshop on purpose.” You’ve likely seen it but didn’t know exactly what to call it. It went viral last year when people took the “Bernie Sanders with mittens” image from the inauguration and photoshoped it badly (on purpose) into all sorts of other photos. The results were predictably hilarious. Bernie sitting on the park bench with Forrest Gump. Bernie sitting in the library with the Breakfast Club. Bernie sitting on the moon next to the planted American flag. The hilarity is in seeing Bernie simply copied and pasted into otherwise iconic images, where he is clearly out of place.

The piece of music under consideration this week can sound a bit like one of those badly photoshoped on purpose memes. Upon hearing The Unanswered Question for the first time, one could be excused for thinking that the music is nothing more than several disparate bits of music haphazardly cobbled together and that everything is out of place. Or that everyone forgot to tune their instruments prior to the concert. Once one understands a little bit about Charles Ives the man, one is better prepared to understand The Unanswered Question.

Charles Ives was born in Danbury, Connecticut, on October 20, 1874. Charles’ father George had been a musician in the War Between the States and was a local cornet player, band director, theater orchestra leader, choir director, and music teacher. Charles received early music instruction from his father and began composing at age thirteen. By the age of fourteen, Charles was employed as a local church organist.

The music lessons that George taught his children were most unusual. He taught his children to sing in one key while he accompanied in a different key. He built instruments that could play in quarter-tones. He would often have two marching bands march together while playing different tunes. Young Charles imbibed all of his father’s love of musical tinkering and would put those things to good use in his own compositions.

After high school, the younger Ives attended the Yale School of Music. He regularly clashed with his composition professor over his strange techniques, his love of hymn tunes learned at camp meetings, and his disdain for conservative compositional techniques. Ives left Yale in 1898 and began a $15-a-week clerk job with the Mutual Life Insurance Company in New York. Eventually, Ives and his friend Julian Myrick formed their own insurance agency, Ives & Myrick.

In 1902, Ives resigned his church organist job and (in his words) “quit music.” His father had taught him that his musical interests would be “stronger, cleaner, bigger, and cleaner” if he didn’t seek to make money from them.1 The son took his father’s words to heart, saying that his children should not have to “starve on his dissonances.”2 With the abandonment of his church organist job, Ives no longer had any formal connections with professional music. But this decision worked in his favor. Because he was making a living in insurance, he was free to experiment and pursue music on his own terms, apart from any monetary considerations.

Ives’ religious life was a haphazard collage of mainline Protestantism, transcendentalism, and revivalism. He counted both Emerson and Thoreau as spiritual influences. In fact, religion was never far from the surface of an Ives composition. Biographer Jan Swafford has made the point, “Ives’s music is as essentially religious as Bach’s, though his faith is very different from the fire-and-brimstone Lutheranism of the German composer. But as with Bach, nearly everything Ives wrote in his maturity was permeated by a religious spirit.”3

Ives was something of a workaholic. He worked long hours at the insurance firm and then worked long into the night on his compositions. Burning the candle at both ends eventually caught up to Ives and his health began to decline. He suffered a series of heart attacks and he composed very little after 1918. His later life in music was spent revising his earlier compositions and overseeing premieres of his works. He retired from life insurance in 1930 and passed away from a stroke in 1954 in New York City.

An unusual music upbringing, a vocation outside music that allowed him to pursue music on his own terms, and a hodge-podge of transcendentalist New England religion. These are the things one must have in mind in order to some sense of The Unanswered Question.

Composed in 1908, The Unanswered Question is a brief work that Ives calls a “cosmic drama.” The piece consists of three very different layers, hence my comparison to photoshoping earlier. The first layer is the string section playing a chorale quietly and serenely in the background. Ives said the strings represented the “silence of the Druids.” They never respond in any way to the other two layers. The second layer is the solo trumpet, which asks again and again (in a different key than the strings) what Ives called the “perennial question of existence.” The third and final layer is a quartet of woodwinds called the “fighting answerers.” The winds scurry around in search of a meaningful reply to the trumpet’s question. Their replies become increasingly agitated until their final, caustic answer. The trumpet asks the question one final time and the winds remain silent as the piece ends.

Here we have Charles Ives’ whole life in miniature. The strings playing the chorale reflecting the religious music of his youth. The trumpet playing in a different key than the strings and asking the question: “what is the meaning of life?” The flutes, in dissonance to both the strings and trumpet, with no real answers. Everything mashed together in a way that would surely have pleased his father.

Earlier I mentioned Jan Swafford’s comparison of Ives to J.S. Bach with both being “religious composers”. The actual religion of the two composers couldn’t be more different. In Bach’s music, everything cohered because He worshiped the Triune God of the Scriptures who caused all things to work together for His glory. He inscribed many of pieces with the words soli Deo gloria—“to God alone be glory.” Ives’ “god” was much more gnostic, vague, and opaque. Ives once defined Christ as a “principle” (such as peace or compassion) rather than a person.4 He said that “being true to ourselves is God.”5

Bach was a master of synthesis. Each voice in a Bach fugue was a little miniature composition of its own. When the individual parts were brought together, they coalesced into grand musical structures that will likely never be bettered. Ives had no interest in synthesizing much of anything. Two instruments playing in different keys? No worries. Just like daddy taught. The sound of two marching bands walking past one another playing two entirely different songs? Sounded like home to Ives’ ears.

Ultimately in an Ivesian universe, the trumpet’s “perennial question of existence” could only remain “unanswered.” God has not drawn near to man in the incarnation of Jesus Christ. Jesus was a “principle” and not a Person that could be known through Word and Sacrament. In fact, knowing absolutely nothing at all about Jesus was no impediment to following Him. As Ives once said, “Many of the sincerest followers of Christ never heard of Him.”6

The Unanswered Question is a fascinating piece of classical music that is thoroughly American but also uniquely strange. Ives had no compositional forebears and practically no one has followed in his musical wake. He was an American original whose music is worth remembering today.

There are numerous recordings of The Unanswered Question. Without a doubt my favorite is an Ives compilation disc conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas and featuring the San Francisco Orchestra and Chorus. Not only does the disc contain a stellar performance of The Unanswered Question but also many of Ives’ songs (sung by baritone Thomas Hampson) and several of his shorter orchestral works.

Spotify | Apple Music | YouTube

—

Classical music is not meant primarily to aid relaxation, studying, or mental focus, although it can do all of those things. It “works” best when an attentive listener gives their undivided attention to the work and “surrenders” to what the composer is trying to convey in sound. Attentive listening goes beyond listening for a pleasing tune or relaxing melody. It goes further up and further in to discover things like harmony, counterpoint, orchestration, text painting, tension, release, and so many other fine details.

Each Monday I will suggest a piece to which observant listeners can attend for the next seven days. Just like other masterpieces, great works of classical music do not give up their secrets easily. Whenever possible, one should give a couple of listens to each week’s piece.

The close resemblance of the title of this series and to the title of the Books of Titans blog and podcast is entirely intentional.

Jan Swafford, Charles Ives: A Life with Music (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998), 85.

Ibid.

Ibid, 302.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.