The year 2020 was a great time to get in a lot of reading. None of us knew what we up against in the early days of the whole “novel coronavirus” thing. So reading was a great thing to do during “15 days to flatten the curve.” But the “new normal” didn’t last—at least not for some of us—and so “real life” had to return and reading time became a bit more scarce.

Nevertheless, I found plenty of time for reading this past year and these are the books I found most enjoyable in the year 2021.

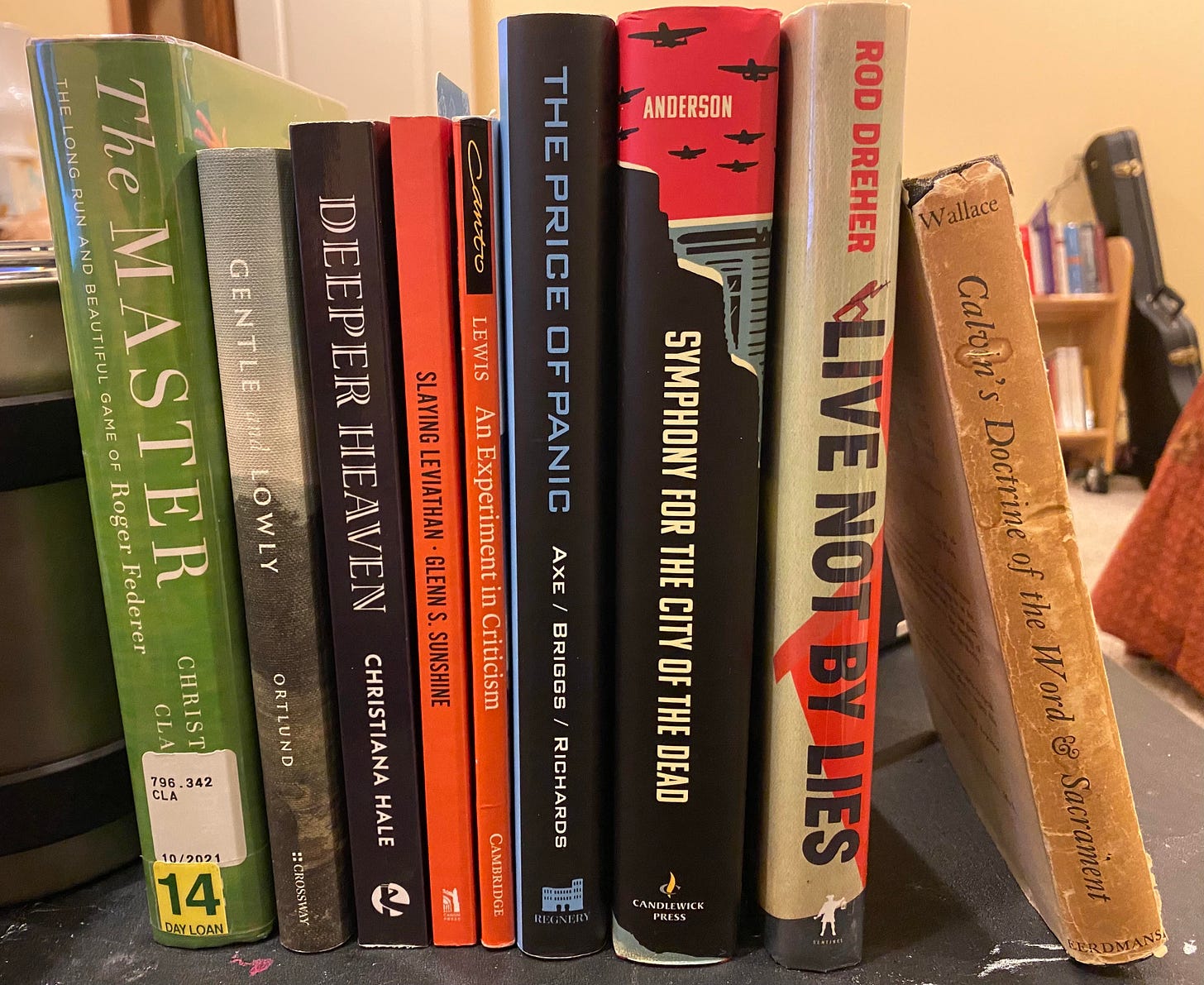

The Master: The Long Run and Beautiful Game of Roger Federer - Christopher Clarey

Clarey’s book hit at just the right time as Roger Federer is winding down his remarkable career and tennis nerds like me are beginning to take stock of the totality of his body of work. The book is far from perfect. Clarey has had unprecedented access to Federer over the year. But that proves to be a liability as Clarey too often opts for personal stories told in first person. That said, this will be the definitive Federer biography for some time and it sneaks onto my list for 2021.

Gentle and Lowly: The Heart of Christ for Sinners and Sufferers - Dane Ortlund

Who among us are exempted from sinning and suffering? None of us. Building on the foundation laid down in Thomas Goodwin’s book The Heart of Christ, Ortlund shows that the heart of Jesus Christ is always moved with compassion toward those trapped in sins or engulfed in suffering. Just a couple of quotes from the book will give you a good taste:

“The cumulative testimony of the four Gospels is that when Jesus Christ sees the fallenness of the world all about him, his deepest impulse, his most natural instinct, is to move toward that sin and suffering, not away from it.” (30)

“Jesus Christ is closer to you today than he was to the sinners and sufferers he spoke with and touched in his earthly ministry. Through his Spirit, Christ’s own heart envelops his people with an embrace nearer and righter than any physical embrace could ever achieve.” (33)

Deeper Heaven: A Reader’s Guide to C. S. Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy - Christiana Hale

A friend of mine (Warren Farha) owns the most wonderful bookstore in the world—Eighth Day Books. When I finished my copy of Deeper Heaven, I took it into the store to show Warren and suggested that they carry it. He had one question, “What would be the selling point for this book?” I replied, “What Michael Ward did for Lewis’ Narniad in Planet Narnia, Hale (no relation) has done for the Ransom Trilogy in her book.” That was all it took. If you’ve never been able to wrap your head around Out of the Silent Planet, Perelandra, or That Hideous Strength, get a copy of Hale’s book to help you out.

Slaying Leviathan: Limited Government and Resistance in the Christian Tradition - Glenn S. Sunshine

This would a great book for a church session to read together as they seek to understand the history of limited government and Christian resistance. The book is pretty thin on modern applications and “what should we do now,” so there is room for wisdom as Christian pastors and elders determine the best course of action in their individual situations. Maybe reading this in tandem with Rod Dreher’s latest book would be ideal (see below).

An Experiment in Criticism - C.S. Lewis

A small book that packs a real wallop. Lewis lays down ground rules for what makes great books “great” and how literate readers read books. His discussion of “using” books rather than “receiving” them has really stuck with me. Also, the differentiation he makes between “literary” and “unliterary” readers is complex and needs to be understood.

“The true reader reads every work seriously in the sense that he reads it whole-heartedly, makes himself as receptive as he can. But for that very reason he cannot possibly read every work solemly or gravely. For he will read ‘in the same spirit that the author writ.’ ... He will never commit the error of trying to munch whipped cream as if it were venison.”

The Price of Panic: How the Tyranny of Experts Turned a Pandemic into a Catastrophe - Douglas Axe, William M. Briggs, and Jay W. Richards

The biggest problem with this book is that came out too early (Oct. 2020). Reading it now feels like reading about the “good ol’ days” when the biggest things one had to worry about were masks, lockdowns, and social distancing at the grocery store. Perhaps the same authors could write a follow-up that deals with vaccines, mandates, and the like.

Symphony for the City of the Dead: Dmitri Shostakovich and the Siege of Leningrad - M.T. Anderson

Easily the most gripping book I have read in a long time. Americans commonly consider World World II from the Allies’ perspective. We don’t often consider it from the perspective of another country, especially from a Russian perspective. Furthermore, we would never think to consider it from the perspective of one classical music composer. The latter is what Anderson does here and the results are magnificent.

The Siege on Leningrad (modern-day St. Petersburg) began on September 8, 1941, when Axis forces captured the only remaining road into the city. The siege didn’t end until January 27, 1944, 872 days after it began. Hitler’s plan was to prevent supplies (especially food) from getting to Leningrad. Once mass starvation had gripped the population, making it a “city of the dead,” the Nazis planned to overwhelm Leningrad with little trouble.

In those first dire days of fear, into a brutal Russian winter, and months of starvation, Shostakovich went to work on his Seventh Symphony. Eventually subtitled “Leningrad”, the knowledge that Shostakovich was working on a new symphony became a source of hope to the beleaguered citizens of the city.

After a harrowing series of rehearsals during which three orchestral musicians died from disease and starvation, Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony premiered in Leningrad on August 9, 1942. The date was chosen for symbolic reasons. It was the date that Hitler had boasted that he would eat a grand feast in the Hotel Astoria after having conquered the city. The music was played that night by emaciated musicians who were barely alive (the siege was still well underway).

Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony not only lifted the spirits of the people in Leningrad but also instilled despair in the Germans. The Leningrad premiere of the work was broadcast on radio and was able to be heard by enemy soldiers. One German soldier admitted about the symphony years later, “It had a slow but powerful effect on us. The realization began to dawn that we would never take Leningrad.” (345)

This book gave me so much to think about in terms of the creation of art under communism, the role the state plays in stifling dissenting viewpoints, being forced to live by lies in order to survive, and the power of music to bolster one group of people while discouraging another.

Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents - Rod Dreher

There are so many strengths to this book. One of the biggest is Dreher’s comparison of our current cultural moment to the pre-revolution Soviet Union rather than the usual lazy comparisons to Nazi Germany. Reading the stories of former dissidents under communism alongside M.T. Anderson’s book made was sobering. The stories they tell are startlingly similar. As I mentioned above, church sessions reading Dreher’s book alongside the book by Glenn Sunshine’s book would have much to discuss.

“And this is the thing about soft totalitarianism: It seduces those—even Christians—who have lost the capacity to love enduringly, for better or for worse. They think love, but they merely desire. They think they follow Jesus, but in fact, they merely admire him. Each of us thinks we wouldn’t be like that. But if we have accepted the lie of our therapeutic culture, which tells us that personal happiness is the greatest good of all, then we will surrender at the first sign of trouble.” (182)

“We cannot hope to resist the coming soft totalitarianism if we do not have our spiritual lives in order. This is the message of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the great anti-communist dissident, Nobel laureate, and Orthodox Christian. He believed the core of the crisis that created and sustained communism was not political but spiritual.” (xiv)

Calvin’s Doctrine of the Word and Sacrament - Ronald S. Wallace

Understanding Calvin’s view of how Christ comes to us in word and sacrament is one of the keys to understanding more deeply the Reformed faith. Especially important is the Spirit’s work in joining us to Christ our Head. In doing this, the Spirit makes us flesh of Christ’s flesh and bone of Christ’s bone.

But equally important in this book is Wallace’s discussion of Calvin on the written word as the Word of God. This sentence in particular is stellar, “If anyone would proclaim the Word of God in the name of Jesus Christ, he must derive the word he has to speak from the witness to Jesus Christ given in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments.” (96) In our day, certain sectors of the Christian church celebrate a certain kind of dynamic vision casting leader who regularly hears from God through dreams, visions, and other means. Wallace’s work with Calvin, written in 1957, is a great corrective to this mindset.

“If we wish to know of Jesus Christ, and to bear witness to Him, it is to this source of the written word that we must turn, both for our necessary knowledge of the historical facts and for our understanding of the meaning of those facts. There can be no other reliable source either for this knowledge or for this understanding than the writings of the law, the prophets and the Apostles.” (96-97)